Oh no, not the bloody white leghorns again! Too late, alas. The memory of the brutal Arkansas chicken adventure was autoplaying in my brain, triggered by the offer of a flock of fifteen hens—free, of course—from someone in the nearby town of Dixon, New Mexico, as published in an email classifieds newsletter I subscribe to:

Does anyone want a flock of about 15 laying hens with a really mellow yellow rooster? Some White Leghorns, Red Stars, a couple Auracanas, and various other breeds. We’re up in Llano and you’d have to come get them in the evening after they roost (say 4:30 or 5). Free!

He makes it sound so simple: just come and get them after they’ve settled in for the night. Of course, you’ll need some cages—or maybe not, if you leap into the abyss like I did over forty years ago.

The events took place at Yellowhammer Farm, the name we’d given to 170 acres of Ozark hills and woods. There was no farm, of course, nor were there any buildings, and for sure there were no yellowhammers—a kind of woodpecker, apocryphal as far as I was concerned—although there was an awful, rutted, rocky track that Madison County called Yellowhammer Road, which crossed a steep corner of the property. “We” in this instance included Larry, Sue, Sylvia, Jim, Bob, and me, all dropping out to live a life of glorious independence on the land. At least I was, and possibly Jim. The others found the pull of civilization far too strong by the fall of ’71. I lasted until Christmas, when I decamped for Austin with Lady the Wonder Dog and six barfing puppies in the old Ford Fairlane my father had passed on to me after I’d ruined the hot rod engine in my ’63 Volkswagen camper bus—a tale of low-restriction air filtration and fine clay dust almost too sad to tell.

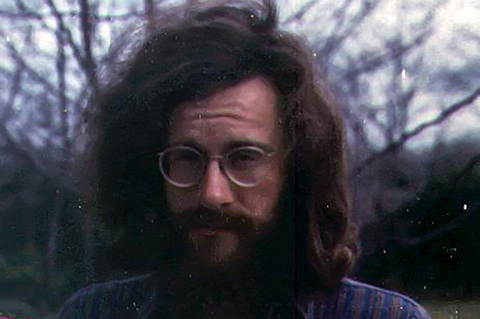

Easter break, ’71: visiting the land before the move

Some day I’ll write the story of the incredible deaf mechanic who built it for me. For that matter, I wish I could fill in the blanks about ’71 and the years that went before for you right now. That much is actually written down already in a half-finished book I started about a dozen years ago, entitled (oddly enough) Yellowhammer Farm. I stopped because it was such a chore to tell the story using pseudonyms the way I thought I had to do, and I came to feel embarrassed for recounting tales of sex and sin that showed me for the shallow whelp I was. It wasn’t bad, though—neither the adventure nor the telling of it. Perhaps the rest are dead now and I could resurrect the project. Publishing some version of the thing would flush survivors out, though, wouldn’t it?

Original animated GIF banner ad to promote the book

For our purposes here, all you really need to know was that by the summer of ’71, six people from Texas in their twenties were living in a motley collection of tents and one hand-built underground home on 170 acres of land they’d bought for fifty dollars an acre about an hour east of Fayetteville and trying their damnedest to make it work. We had a garden, foraged in the woods for wild persimmons, and ate communal vegetarian meals under a canvas awning beside a hand-dug well. There wasn’t any dope because we couldn’t find any. There wasn’t any sex because Sylvia refused and Sue was married. There wasn’t any booze, because, good God, who drank? Nudity was common, however, and we’d all ride down to the river or a nearby creek to bathe. We had no electricity or telephones. Whippoorwills shrieked scarily in the woods at night and wild hogs rooted in the leaves. There were three substantial streams and several waterfalls. It took about an hour to get to town unless we headed for the closer county seat, which we avoided if we could because the locals mostly loathed us. My contribution to the immediate ambience was ordering an Earth flag from the Whole Earth Catalog (where else?) and mounting it on a pole. The nearest fellow humans were several miles away, and that was fine with us.

(Yes, but what about the chickens?)

Living so far away from groceries and having no refrigeration other than hanging a bucket down the well meant that we often dreamed of chickens. Not to slaughter for their meat, but for the eggs. Dreaming is how we did it, too, instead of actually going to the trouble of procuring hens. When the friend of a friend announced that he was giving away a flock of leghorns, we were ready with Larry’s pickup truck.

On the way to where the chickens were, the question of how were we to carry them came up. I think we figured we’d just hold onto them, although I doubt more than one of us (me) had ever touched a living chicken in our lives. I also wondered how we’d catch them in the first place. As it turned out, this was fairly easy: we simply grabbed a few old Army blankets and threw them over the birds, then scooped them up and sat down in the back of the truck with their little heads poking out. A rooster was also part of the package. Bob was proud to be custodian of the cock, as it were, but found the bird was dangerously prone to pecking and covered up his head.

It was a very hot day. When we finally returned home, the rooster was good and dead, and Bob was mortified. He buried the hapless rooster next to his tent up on the “mountain” and named his holding “Cocksgrave.” There was something of an Anglo-Saxon literary bent at work with Bob that everyone accepted. I had my reservations, but when he left to go back home to Texas, he sold me his .22 rifle and a saxophone for twenty bucks and I was mollified. (I still have the rifle with his name carved in the stock.)

We had no chicken coop, but I’d erected a pen of sorts with sticks and chicken wire (obviously), which the birds promptly escaped by taking flight and roosting in the trees. This state of affairs lasted for several weeks, and there was little we could do. They didn’t seem to mind the absence of the rooster and laid eggs wherever they wanted. Inside hollow logs or under piles of leaves were favorite spots, and if we found them, we had eggs. In the interest of efficiency, I eventually built a stronger pen and had a flash of inspiration as to how to keep them there: all we had to do was clip their wings! It sounded like a normal chore, like trimming your hair, for instance. That none of us had ever done it was no obstacle, and I volunteered.

We collected the chickens by spreading cracked corn on the ground and nabbing them with blankets again. Figuring that all I had to do was cut them down to a size that prevented the birds from flying, I used a pair of scissors to cut the wing feathers back as far as I dared, and soon we had a flock of hens with little stubby wings. Which quickly started bleeding… Who knew that living feathers had blood vessels? The bleeding wasn’t heavy, but the birds were snowy white, and soon they all showed bloody stains to punctuate my guilt. The chickens didn’t seem to mind, however, and at no point demonstrated any pain or obvious discomfort. In fact, the maiming didn’t slow them down at all: when all the corn was gone, they promptly flew right out of the enclosure and back into the trees! All they had to do was flap a little harder, and they were free.

Christmas with the folks in Houston, ’71: the vibes were not so high

For the rest of that summer and into the fall, the chickens led a liberated life, although we rarely saw them. I’d go on egg hunts close to camp and sometimes find a dozen at a time. Amazingly, these eggs were always good—not rotten—and their discovery was usually an excuse for feasting. What I don’t recall is exactly what happened to our chickens by the time winter weather had set in and I’d abandoned ship. I hope somebody took them. If not, the foxes and the weasels caught them one by one. My world was growing smaller then, and I simply might not have noticed. By that time I was all alone up in the woods and something like a saddhu. If I had stayed, my spirit would have melded with the rocks and trees and I’d have been a goner. Before I left that winter, I collected bird nests from the land and took them home to Houston for Christmas presents. The only one who liked her nest was my sister Teresa, of course. Whatever was I thinking?

Years later my father told me that all I’d had to do was trim a little off of a single wing, and the resulting imbalance would have kept the birds from flying. He also initiated me in the mysteries of the chicken hook, a simple implement that does away with tossing blankets over running chickens like a fool. I could make one for you now from a coat hanger and a stick, just say the word.

.png)

I wish I had my chickens again. There’s nothing like a fresh organic egg! Do the chickens come with equipment, like laying boxes and chicken wire for an enclosure?

Are you kidding? Have you ever been to Dixon? 🙂 But no. I edited the ad somewhat, but none of that was mentioned. There’s a phone number, of course.

I always enjoy it when you talk about Arkansas. I have a ton of chicken stories, too. Chickens still fall off of the Tyson trucks sometimes and the people who rescue them from beside the road end up with good chicken stories, too. One of our rescues grew up to be an enormous white fluff ball we names Snowball. Poor guy. He was at the absolute bottom of the pecking order.

Glad you like it when I talk about Arkansas. (I know that’s where you’re from, of course. ) My impression is that these stories don’t affect that many others. Maybe it’s cultural. But chicken stories, hoo boy. I didn’t know the Tyson trucks lost birds! Arkansas is big on raising chickens and such. There was a farm down the road from us that had at least a thousand turkeys. I used to stop and stand beside the fence, and all of them would gather around.

You must log in to post a comment. Log in now.